I was wrong! But emigrants will get voting rights…eventually

Friday, February 26th, 2016I fess up: I’m a lousy prognosticator. In 2011, I predicted that this would be the last general election that emigrants wouldn’t be voting in. It sounds so naively optimistic now, I realise. But we were in the mood for reform back in those post-crash days! I got caught up with the heady excitement of it all.

In the interest of transparency, I am copying my 2011 article in full below. I won’t make any predictions regarding the timing again, but I am certain that Ireland will eventually take its place among the nations of the world in allowing its nonresident citizens to vote. In the meantime, I’ve joined in with a few others to start work on a new venture toward ensuring that it happens – we’re just at the start of it, but you can join us over at VotingRights.ie and follow us on on our shiny new Twitter feed at @VotingRightsIE.

7 reasons this will be the last election Irish emigrants won’t be voting in

I’ve been writing about emigrant voting since about 2006. When I started, it seemed that any victory in the battle for the emigrant vote was a long way off. I don’t believe that anymore. In fact, I believe we’ll see emigrant voting by the next general election. Here’s why.

- We see them everywhere, still. Emigrants may have left, but they’re still up there on our Facebook pages, Twitter feeds, Skype contacts, and even our TV screens. They’re joining the chat about Fianna Fail, Lucinda Creighton, rugby, The Rubberbandits, you name it. Some people still try to make the argument that Irish people abroad aren’t staying informed, but it’s a fairly obvious denial of reality: expats have the same access to most of the same media that any of us in Ireland do. They’re going to keep consuming this media, and they’re going to keep appearing in it. It’s going to be harder and harder to pretend that their voices are ill-informed or irrelevant.

- The truth is out: emigrant voting isn’t the preserve of a few countries. In reading the Dáil debates of the past, one of the most striking features is how little actual knowledge there was about how many countries allowed their emigrants to vote. People referred to countries like France, the UK, and the US as if these were anomalies, and emigrant voting were some kind of peculiar national quirk, undertaken by these few radically democratic nations. Now, however, we know that emigrant voting is a global democratic norm: thanks to a 2007 study by IDEA called “Voting from Abroad, the International IDEA Handbook, it’s fairly common knowledge that more than 115 countries and territories allow their expats to vote. This includes nearly all developed nations, and nearly every other EU country. [2016 note: since 2011, the trend has only accelerated.]

- Our current situation is irrational. Our policy-makers want to be global leaders in diaspora relations, and, in truth, Ireland is pretty close. The global Irish community is loyal, active, in touch, and engaged. We value their economic contribution: the 21st-century version of remittances includes such activities as business networking, opening new markets to Irish companies, and directing FDI. Our global networks supporting Irish sports, heritage and culture are vibrant. Yet when it comes to the emigrant vote, we’re seriously out of step with the rest of the world. We section off politics as the only realm of Irish life that’s off-limits to our overseas citizens, while most nations treat political engagement with their diasporas as a basic tool of these relationships.

- It’s only fair to give them a say. Occasionally, Irish residents will argue that emigrants should not have the vote because they don’t want non-resident citizens making decisions that affect people living in Ireland – yet they don’t consider that the government is also making decisions that affect overseas citizens.What are those issues that concern emigrants? Many are the same issues that might concern any other Irish citizen, but there are a few that are of particular interest to the Irish abroad. Some Irish people pay taxes while abroad; some who inherited family homes, for example, have had to pay the tax on non-primary residences introduced in recent years. Some of our most vulnerable emigrants (many of whom are from the 1950s and 1960s generation, who saved little for themselves while sending millions back home) depend on programmes paid for out of the emigrant support services budget. Others receive Irish pensions based on contributions they made while working in Ireland. Any expat at any time may find themselves in need of consular protection, as the troubling events this week in New Zealand and Libya showed.

If you’re Irish and you want to come home, an economy that will enable you to return home to a job will be of paramount concern. Some of those coming home have had to seek social welfare assistance, yet thousands of returning emigrants have been denied this under the habitual residence condition – despite assurances on the introduction of this legislation that returning emigrants would not be affected. Civil partnership and spousal immigration legislation will affect whether an emigrant can return home with his or her partner.Who in Ireland is speaking up for the interests of our overseas citizens in these issues? Emigrants need their own voices heard. - The 1998 changes in the constitution deterritorialised the Irish nation – and firmly positioned our overseas citizens within it. The new Article 2 says it is “the entitlement and birthright” of every Irish citizen “to be part of the Irish Nation”. As Article 1 tells us, it’s the Irish nation that has the “inalienable, indefeasible, and sovereign right to choose its own form of government, to determine its relations with other nations, and to develop its life, political, economic and cultural, in accordance with its own genius and traditions”. How can one segment of the Irish nation take away the inalienable, indefeasible, and sovereign rights of another? The question needs further exploration.

- The bogeyman of The North is dead. For the last few decades, the debate over emigrant voting rights was overshadowed by the fear in some circles that there was a radicalised overseas electorate lurking within the heart of Irish-America, ready to launch gunmen into office. If this were ever true, it’s certainly not now, however many fears may linger in the minds of those Irish residents who cling on to their outdated, stereotypical notions of the Irish in America. Brian Cowen acknowledged it: The Northern Irish peace process united Irish opinion with the diaspora. The Irish in America played an enormous role in facilitating that peace process, and it’s time to get over the idea that an irrational fear of our own citizens is a reason to disenfranchise them.

- European institutions are starting to take an interest. While the EU has always regarded expat voting as an issue of national competency, there have been several international bodies that have taken steps toward emigrant voting rights recently. The European Court of Human Rights, for example, recently ruled that Greece needed to implement the emigrant voting provisions it had introduced into its constitution some decades back; while the decision was primarily based on the Greek constitution, it also took into consideration that out 29 of 33 Council of Europe countries had implemented procedures to allow voting by overseas citizens. The court is currently dealing with the case of an elderly English man living in Italy who is challenging the UK’s 15-year time limit on expat voting. [2016 note: Harry Shindler lost his case, but the Conservative government has promised to eliminate the time limit – though not before the Brexit referendum.] These kinds of cases aren’t going to go away, and it’s likely that these types of challenges will increase.

Meanwhile, the 2010 European Commission report on citizenship has indicated that the EU will take a look at this issue in the future. The report pledges that the Commission “will launch a discussion to identify political options to prevent EU citizens from losing their political rights as a consequence of exercising their right to free movement”. With the increasing international trends toward engaging overseas citizens, European institutions will be more likely to be active in these issues in the future. [2016 note: The Commission has issued that guidance, which criticized Ireland for being among the few European nations that don’t offer emigrant voting rights.]

With the mood for reform sweeping Ireland, I’m confident that the many proposals that have been made aimed at giving emigrants a voice will result in real change – and if the new government doesn’t implement these kinds of changes, we’ll just fall further out of step with the rest of the world, and with the legitimate desires of our own citizens for a say in the government of their own nation. We need our emigrants. We can’t expect the same level of loyalty from our our overseas citizens as we did in the past if we continue to refuse them the basic right that nearly every other developed nation in the world would give them.

Generation Emigration surveys emigrants on voting, politics

Wednesday, February 24th, 2016The Generation Emigration blog of the Irish Times is currently running a survey aimed at exploring the political views of the Irish abroad. It’s just a few questions inquiring about time away from Ireland, attitudes about emigrant voting, and favoured political party. The survey will be up until noon on Thursday. Answer it on the Generation Emigration website.

Sign the #NoHome2Vote petition!

Monday, February 22nd, 2016Uplift has started a petition and social media campaign to support emigrant voting rights ahead of Friday’s general election. Sign it on their website, Uplift.ie.

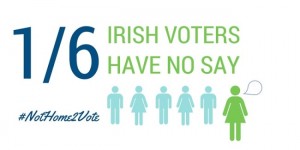

Noting that 1 in 6 Irish voters won’t be able to cast their vote because they’re living overseas, they say “#Uplift has teamed up with organisations fighting for the rights of Irish emigrants across the world to make sure that the next government promises this will be last election so many Irish people are barred from voting.”

They note the excitement over emigrant participation in last year’s referendum on equal marriage, and yet Ireland remains one of three countries in the EU that denies citizens abroad the right to vote:

Together we can use this election to force voting rights for emigrants onto the agenda of a new government and turn promises into real action.

The first step is to gather as many voices as possible over the coming week and to make sure both voters and candidates feel the strength of our voice the day before the election. This is the day political parties and candidates are not allowed on the airwaves so it’s a perfect moment for us to flood social media with a message from Irish emigrants living in every corner of the world. We have a great chance of making sure voting rights for emigrants gets on the table when the new government sits down to plan the next few years.

IrishCentral.com announces “Digital Influencers Top 40”

Wednesday, September 23rd, 2015IrishCentral.com has announced their “Digital Influencers Top 40” list. The list celebrates “40 of the most innovative, talented and hard-working Irish-born and Irish-American individuals leading the way in advertising, media, marketing, tech, e-commerce and a range of other entrepreneurial ventures and services”.

You can see the entire list here – I’m happy to say I’m included on it.

OECD weighs in: emigrant vote would benefit Ireland, citizens abroad

Wednesday, September 23rd, 2015The OECD is the latest international body to weigh in on Ireland’s disenfranchisement of its expats. In their latest economic survey, the organisation says that Ireland is out of step with the rest of Europe, and both citizens and the nation are missing out:

One aspect with significant room for improvement concerns emigrant’s political representation and right to vote in Irish elections. Ireland is one of the few countries in Europe not to offer some form of suffrage to its citizens who live abroad (Honohan, 2011). The vast majority of countries have electoral systems allowing emigrants to participate in some ways in elections. Voting can allow states to build and retain highly productive connections with diaspora groups (Collier and Vathi, 2007). Political participation is positively associated with well-being (Frey et al., 2008 and Blais and Gelineau, 2007). Thus, civil and political engagement is one of the building blocks of the OECD’s Better Life index. Allowing for the participating of Irish emigrants in domestic electoral process would reinforce their attachment to Ireland, would bolster the linkages that Ireland has been successfully building over the years and would make a positive contribution to emigrant’s well-being.

Calling former emigrants to Australia – complete a ten-minute survey!

Wednesday, July 1st, 2015A researcher in Adelaide, Australia writes of her eagerness to reach anyone born in Ireland or Northern Ireland who has lived in Australia and since departed. She would be grateful for responses to a short survey investigating aspects of the immigrant experience in Australia as outlined below:

This study is being undertaken to gather data from persons who have travelled from Ireland/Northern Ireland to Australia on a long-term temporary or permanent visa and departed from Australia again. The data will be used to investigate the impact of immigration policy and social media and technology on the migration experience. Impact is measured in terms of return visits to Ireland, migrants’ perceptions of connectedness to ‘home’ and the settling in process with regard to family, social networks and working life. Pre-migration sources of information about Australia and measuring expectations against the reality of migration are also covered.

It takes around 10 minutes to complete and you have the option of participating in a personal interview conducted by phone or in person. If you can help in this regard, please leave your details in the space provided.

To complete the survey, visit the survey website.

The survey has Human Research Ethics Approval (HREC Approval No: H-2014-234).

« Previous Entries